Sugar is having a really tough time at the moment with government, pressure groups and Jamie Oliver all queuing up to declare it Public Enemy Number One. In the words of John Yudkin sugar is perceived to be ”Pure, White and Deadly.” So I would like to present the case for the defence.

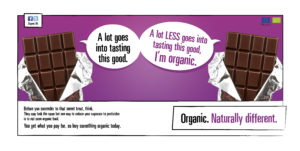

Let me declare an interest: I do not work for a sugar supplier, and I have never done so. What I have done is spend many years of my life attempting to replace sugar in foods, notably when I was at Whole Earth Foods (1986 – 1995) where I helped Craig Sams develop a successful range of food and drink grocery staples sweetened with apple juice in place of sugar. During that time we also came up with the idea for Green & Black’s Organic Chocolate: we quickly established that sugar was the best sweetener to use in this application, which is why the chocolate brand was created as entirely separate from sugar-eschewing Whole Earth.

So what benefits does using sugar bring? Depending on the application some or all of the following: sweetness, mouthfeel, bulk, texture, stability, moistness and flavour (neutral on its own but transforming into caramel via the Maillard reaction). Plus it is an all-natural product that humans have consumed safely for thousands of years and it readily can be produced to organic standards and under Fairtrade conditions.

Nonetheless excessive consumption of sugar is now associated with many health problems which are escalating so fast that the NHS is struggling to cope. Most significant are diabetes, dental decay and obesity. Only the most flat-earth industry insider could argue against reducing sugar consumption as a way of improving the health of the nation.

Accordingly In March 2016 the Treasury (not the Department of Health) announced plans for a levy on sugar used in soft drinks, to be implemented from March 2018. By the time the levy was introduced average sugar content of branded soft drinks had fallen from 6.8g/100ml to 5.6g/100ml with 150 products being reformulated to escape the levy completely. The Treasury is claiming this as a victory: although anticipated levy income has fallen from £750m per year to around £250m, the only branded soft drinks remaining in the high sugar-levy category are regular Coke and regular Pepsi. With the honourable exception of Cawston Press and a few other artisan drinks producers reformulation was largely achieved by replacing sugar with intense sweeteners such as saccharine, acesulfame-k or aspartame. Artificial sweeteners are a more cost-effective way of achieving sweetness than using sugar, so the industry was more than happy to reformulate.

Could a levy on the use of sugar in food achieve the same miraculous results ? Public Health England (PHE) is currently working with the food industry in order to encourage sugar reduction using three strategies: reduction in portion size, substitution of healthier products and reformulation of mainstream recipes. Year One results reported in May 2018 do not suggest that the programme has got off to a good start. Over eight key market sectors – biscuits, breakfast cereals , chocolate, ice cream, desserts, confectionery, sweet spreads and yoghurts – very little progress in sugar reduction has been made in the first year. The target was -5%, actual results achieved were -2%. Two categories were unchanged, five made modest reductions and one (desserts) actually increased in sugar content over the year. To be fair, PHE understands that reformulating cakes, biscuits and chocolate is a lot more technically challenging than replacing the sugar content of soft drinks with an intense sweetener. Industry lead times mean that Year One results were unlikely to contain much evidence of product reformulation. Year Two results (due in May 2019) will have to be significantly better for PHE to maintain its current position of working collaboratively with industry. If the PHE initiative its deemed to have failed then legislation and a sugar levy on food products is looking highly likely.

The PHE figures do not yet reflect how hard the UK food industry is working to reduce the sugar content of some of its best sellers. Exhibit One: Nestle Wowsomes. PHE has encouraged chocolate manufacturers to work to a maximum sugar content that averages out at 43.7g per 100g by 2020. For dark chocolate and high cocoa solids milk chocolate this is manageable but white chocolate presents a greater challenge. Nestle are to be congratulated on the elegant technological solution they have delivered using “hollow sugar crystals” and other all-natural ingredients.

Traditional Milky Bar contains 52.6% sugar: Wowsomes is only 30.6%, justifying the prominent onpack claim of “30% Less Sugar!”. However the energy content of the bars is almost identical – 543 kcals per 100g for traditional Milkybar, 527 kcals per 100g for Wowsomes. The most significant difference between the bars is weight: traditional is 25g, Wowsomes is 18g. Wowsomes comes in at 95 calories per bar as opposed to 136 calories for a traditional Milkybar. The most significant cause of this difference is the reduction in bar size. Consumers will undoubtedly be impressed by a bar that proudly proclaims 30% Less Sugar and still tastes sweet. However on a weight-for-weight basis Wowsomes is only 3% lower in calories than a traditional Milkybar. Next year Cadbury’s are launching a Dairy Milk with a 30% reduction in sugar, to be replaced by an unspecified vegetable fibre (possibly inulin). It will be interesting to see whether any calorie reduction ensues.

My major reason for supporting sugar is that the alternatives are worse. All intense sweeteners have been banned somewhere at some time because of health concerns. The nadir was the animal testing trials conducted by GD Searle on aspartame, which featured laboratory rats coming back from the dead. The exception here is stevia, a plant extract which is the nearest thing we have to a natural intense sweetener. The problem with stevia is its flavour profile – some people perceive it as metallic, it can taste of liquorice and it takes a while for the sweetness to come through. All intense sweeteners require the addition of a bulking agent to make up for the physical amount of sugar eliminated from the product.

The bulk alternative sweeteners also offer technical challenges. The polyols – xylitol, mannitol, sorbitol et al – do not contribute to tooth decay and are lower in calories than sugar. This is because they are not recognised in or digested by the human gut. On the way through the body they pick up some extra moisture, resulting in osmotic diarrhoea if more than 20g of the polyol is consumed per day. The legal requirement to put this warning on product labels has resulted in reduced enthusiasm for their use. The polyols also have a negative heat of solution which means if eaten in solid form they make your mouth go cool: fine in a mint chewing gum, weird in a Mars bar.

Other sugar replacements include honey, agave syrup, fruit juice concentrates, maple syrup and malted cereal syrups. All contain at least some simple sugars and each has a distinct flavour which may or may not work in a given food application. At Whole Earth we selected a low acidity apple juice concentrate which we then passed through charcoal to reduce colour and flavour further. The neutral tasting syrup that resulted was a long way from an apple.

The current situation with sugar is analogous to the margarine wars. For decades food manufacturers and their in-house nutritionists attempted to argue that cheap hydrogenated and inter-esterified vegetable oil was nutritionally superior to butter due to a very selective narrative about saturated fats. Today butter is in the ascendant as a delicious tasting traditional high quality product to be used in moderation. Unless you are vegan, where thankfully there are now dairy-free spreads that are manufactured without high levels of trans-fats.

I believe that sugar is currently the least worst sweetener that the food industry has at its disposal. However a replacement for sugar would still be very welcome. What is needed is a single, all-natural ingredient that can replace sugar weight-for-weight with no other additional ingredient being necessary. This ideal sweetener could be used in a wide variety of applications. It would have similar sweetness to sugar on a weight-for-weight basis and would deliver other health benefits into the bargain. It could be produced under organic and Fairtrade certification. It would read well on an ingredient list and be approved by governments, pressure groups and Jamie Oliver.

Does such an ingredient exist?

Not as far as I know.

But watch this space…